Ethnographic Study: The How At The Heart of Customer Intimacy

In the 1st part of this two-part series on “Why Ethnography is the Beating Heart of Customer Experience,” we focused on why there is a need to get to know your customers more intimately than a passing aquaintance with Surveymonkey can offer: getting involved and in-depth gives you the meaningful insights that your competitors will find hard to uncover and most likely to ignore.

Here, in Part II, we’re all about action, offering up practical tools and steps—a blueprint for conducting your own ethnographic study as the methodology for creating meaning and achieving true customer intimacy. Enjoy, and get ready to dig in.

AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY: HOW?

You may not have a formal education in anthropology or sociology, but a novice ethnographer can be highly effective by being empathetic and approaching the ethnographic study with rigor. With an open mind and a sincere interest in all things cultural, pack the following on your journey to the heart of your customers:

– A passionately curious mind

– A non-judgmental, open attitude towards all you see and hear

– Devotion to delving deeper into cultural phenomena

– The willingness to probe for deeper meaning, no matter how uncomfortable

– An ability to unselfishly listen and observe

– Deep empathy for others

Ethnographic research is concerned with understanding individuals in the context of their daily lives and framing their behaviors within the environment and community that surrounds them. But it’s not just a single ethnographic research method—it’s a collection of tactics that researchers use to gain insight. Typical methods include self-documentation (cultural probes), in-context immersions, and in-depth interviews. The point is to focus on capturing and understanding the participant’s daily life, personal background, as well as their repertoires and the activities they undertake within the space you’re investigating. It’s complex, it requires patience and a finely tuned ear, and we have no doubt that you, being the real-live human that you are, can do this!

So, if you’re ready, here are four steps to help you get in-field and begin to conduct your own ethnographic study.

STEP 1: FRAME THE PROBLEM

Before you get started, it’s critical you correctly frame the problem you’re trying to solve. If you’re not structure and hypothesis-driven, you’re not going to get the rigorous, fact-based analysis you seek. So, start with what you learned in high school—an initial hypothesis (or multiple theories depending on the breadth of the problem). You’ll work toward proving or disproving it/them in the field. This might seem counter to the spirit of qualitative research—gaining as much insight into a person’s life or a given issue without pre-ordained frameworks or bias, right? Well, you’re likely on the clock and working with a finite budget, so you’ve got to focus your resources somewhere. Having a set of hypotheses is an excellent way to rein it in.

Getting down to it, we recommend that customer experience (CX) teams concentrate on answering three simple questions to form their initial hypotheses prior to engaging in any ethnographic study:

What Do We Know? Take a survey of insights you already have and facts that can support those, garnered from your industry experience and prior research.

What Do We Think We Know? These are the insights or working hypotheses that need to be either validated by or challenged via additional research and learnings.

What Don’t We Know? Take stock of the knowledge gaps that need to be filled with primary research and learnings.

We find these three simple questions are excellent at sparking the right “strategic conversations”—those valuable chats that get the team on the same page regarding the key issues they’ll seek to understand in-field. A common set of shared intentions lead to action, and who doesn’t want action?

STEP 2: RECRUIT THE RIGHT RESPONDENTS

An excellent, well-executed ethnographic study begins during recruiting—not after you enter the field (despite popular belief). Your sample has a huge bearing on the data, and the risk is even higher in business ethnography where sample sizes are smaller with fewer opportunities to get it right. (Unlike in a quantitative study where volume speaks, well, volumes.)

Our biggest tip: be wary of “professional participants”: recruiting agency regulars who through extensive participation have been trained on how to answer researchers’ questions. It never used to be a problem, but as the field of ethnographic study becomes more mainstream as a research method, these “pros” seem to show up more and more.

A great way to overcome this is to over-recruit and then hold brief phone screens with each respondent to see if they are indeed knowledgeable of the subject you are studying. They should be articulate and forthcoming with information, and to be a good candidate, you must have the confidence that you can answer “Will they let me in?” with a resounding YES!

We can’t emphasize enough how critical recruiting appropriate and inspiring participants is. No two studies are the same, so don’t rush, and be sure to give this step some deep thought. The research questions you are trying to answer typically shape the selection of the place and people you wish to study, but there is another level of nuance or strategy you might want to consider.

Here are three recruiting strategies we frequently use at THRIVE:

Tap Into Your Segmentation

If you have a formal market segmentation in place at your organization, this is an excellent starting place for sampling and recruiting for your ethnographic study. Market segmentation studies are typically based on quantitative data (useful for determining market size), provide a stereotypical sketch of target groups focused on consumption and ownership, and are quantitatively validated. An ethnographic study is an excellent way to go deeper, it’s micro-targeting on an emotional level and gives you a more holistic understanding of your audience, their values, needs, daily routines, problems, fears, motivations, opinions, aspirations, aesthetic preferences, and relationships. All the granular information product and service developers need to create meaningful offerings. We’d recommend you recruit 12-15 respondents for each market segment you’re wishing to understand. That number is perfect for getting a deeper, more holistic view of your customers, as well as the right information to engage and inspire stakeholders to create solutions that really make sense.

Recruit the “Extremes”

For an ethnographic study to stimulate new opportunities, it is useful to take a look at people who represent the extremes of consumption. We call them “Category Connoisseurs”—extreme participants who by their seemingly severe views can help forecast the future of new products and services. How can they be so clairvoyant? Because what goes on at the extremes of consumption often helps define what’s next—the trajectory a technology, behavior or category will take in the future. Understanding what lies ahead for commerce is dependent on understanding social change, and social conventions often begin as “fringe” thinking. Category Connoisseurs take technologies, products, and behaviors to new places; they are social and technological innovators, and an excellent source of both insight and a “North Star” for new paths. So always consider extremes as a part of your recruiting strategy. Look for deviance. It can be incredibly empowering.

Find Your Lead Users

The Lead User methodology has been around for a long time, and it’s a valuable strategy if you are studying consumer behavior in rapidly changing product or service categories, especially “high technology”. Lead Users are not as cutting edge as extreme users, but they do have the real-world experience needed to problem-solve beyond the passive consumer and exhibit serious needs that are likely to become mainstream in the months ahead. These need-driven innovators typically solve whatever problem they are experiencing through their own means, and as a result, are excellent at providing new product concepts and design data. They are a great source of unarticulated behaviors and desires the rest of the population may have an interest in but are easier to observe and identify because they feel the effects more powerfully than others.

The bottom line: go wide. In all of your recruiting efforts, consider participants as a spectrum and fill all the slots from extreme to the middle to capture the full range of behaviors, beliefs, and perspectives, even if you’re working with a relatively small number of participants.

STEP 3: PLAN AN APPROACH

Define The Purpose of Your Ethnographic Study

Never go into the field without a clear purpose—a bulletproof reason you’re conducting your ethnographic research. The best way to be sure? A solid purpose statement.

It’s a simple thing really—and a great way to get alignment with all your stakeholders before setting foot in the field. A good purpose statement should be a single sentence. It should have no more than 30 words. And it should begin with the word “to” and include a qualitative verb to make it action-oriented.

Here’s an example of a well-executed purpose statement:

“To gain an understanding of millennials’ attitudes towards home cleaning and explore their habits, repertoires, strategies for maintaining a clean household and identify new potential opportunities for time-saving products.”

To ensure your purpose statement is clear, ask yourself:

1. Does the purpose start with “To” followed by an action verb?

2. Does it specify who the respondent is?

3. Does it indicate the arena in which the study will take place?

4. Does it define the outcome?

Answer yes to all of them, and you’ve got your purpose statement. Alignment is yours.

Build A Roadmap

An ethnographic study should have a discussion guide—a roadmap that organizes your inquiry but also helps to define clear buckets for analysis. We structure our discussion guides to build rapport with respondents—into four main sections that reflect the natural flow of conversation:

1. Introduction

This part is centered on getting the logistics out of the way (incentives, the time required for the study, etc.), introducing yourself and laying out the framework and tools for the study. Key activities here may include things like homework for your respondents:

Pre-work: Self-documentation Review

Before beginning your ethnographic study there can be a tremendous value in getting respondents to complete what’s known as “Cultural Probes” before the actual ethnography takes place.

While it might be nice to move into your respondent’s home for two weeks (especially if you’re studying a subject that is temporal or typically takes place over an extended period of time, like chronic illness, home improvement, business processes or financial investing) in business ethnography you do not have the luxury of time. So getting participants to research their own lives by collecting textual and visual information in booklets, video diaries or digital logs can help you target the areas you really want to talk about once you are in the workplace or home. It is also great for opening a more personal and deeper tone in conversation. With the awareness self-study and added context brings, an expectation has been set, and conversations tend to be more focused, with participants typically ready, enthusiastic and eager to talk about themselves. The added benefit here is that you have also added some objectivity to the way they live their own lives by making them more mindful of their daily routines and rituals.

2. Rapport and Reconnaissance

This second phase is where you begin to get personal with respondents, conducting a home or workplace tour as a part of your ethnographic study is critical to understanding the context of their lives so you can reference it later in your exercises or discussions. This phase is about getting to know the respondent through low-anxiety questions and participation. Here, you might do some reconnaissance.

In Context Immersion: The Home or Workplace Tour

Immersing yourself in the context of the life of the person you are studying is critical to human-centered design in that nothing helps a person understand another better than walking with them on their daily journey, witnessing pain points firsthand, as well as the opportunities they provide. Asking participants to give you a tour of their home or workplace (the context you are studying) and to tell about how they use particular products or a given space, on what occasions and with whom, is useful for revealing people’s activities and perceptions, as well as the impact spaces and artifacts have on their behavior. This look-see is critical for uncovering recurring patterns of behavior to identifying opportunities for future growth.

3. In-Depth Investigation

Phase three is where you should begin to triangulate the data you have already collected in the study and focus on understanding the contradictions that exist in a respondents’ life—those pesky “say-do” gaps—as well as workarounds they seem oblivious to but that hide true commercial opportunities. Key activities in this stage may include:

Enactment

This is asking participants to act out specific rituals, tasks, and activities they undertake as part of their daily lives. It’s particularly useful for debunking assumptions, as well as revealing how people conceive of and order their repertoires and routines around specific products and services. You can even enhance this with process mapping to gain a better understanding of the use patterns consumers adopt, the challenges consumers have, and the workarounds they’ve adopted to get insight at a very granular level.

In-depth Interviews

Individual in-depth interviews are critical to most ethnographic research since they enable a deep and rich view of the behaviors, reasoning, and lives of people you are studying. These should always be conducted in context and in an open-ended and exploratory fashion. As well, “doing” not just “saying” makes the conversation less abstract and gives respondents the freedom to demonstrate and share their experiences with the objects they use in real-time. Being up close and personal gives you a great vantage—the ability to see the objects, spaces, and potentially the people respondents talk about during the interview.

Storytelling

Telling the stories of our lives is so fundamental to our nature that we are largely unaware of its importance. As a result, this makes storytelling a powerful and very natural tool for ethnographers. As humans, we think in story form, speak in a narrative, and bring meaning to our lives through stories. Through telling stories, we reveal important issues and opportunities in our daily experiences, and as such, asking respondents to go beyond the present moment in time to recount their experiences interacting with a service or a product enables them to see it subjectively and share cherished experiences and insights. It is this subjective perspective that tells us what we are looking for in all our research efforts. Within the story, we gain a clearer perspective on personal experiences and feelings, which in turn tells us how to bring greater meaning to people’s lives, giving us complete case histories of problems and future desires.

4. Closure

The process of wrapping up an ethnographic study offers an opportunity to drive towards specific issues and fulfill your study’s purpose. It is your final chance to use all the rapport and trust you have banked with a respondent to really investigate deeply and look for the contradictions between what people say they do and what they actually do—that all-important say-do gap that both exemplifies the contradictions of human behavior, but also provides us with insight into hidden needs and new opportunities. Key activities in this stage may include:

Triangulation

The end of the ethnographic study is the opportunity for you to review the engagement and surface any contradictions that remain unspoken and require further contextualization. Triangulation as an activity is not just about validation, but about deepening and widening your understanding by cross-referencing all your data. It’s your final opportunity to bring together all the viewpoints and standpoints you have collected through different methods (interviews, observations, enactment, storytelling, and physical evidence) and begin to not only validate but dig deeper in any areas you feel remain contradictory and unanswered. Note this can be difficult to do for the lead ethnographer (who has been guiding the study) to do, which is why you should always work in tandem with another ethnographer to analyze data in the moment if possible.

STEP 4: COLLECT THE DATA

Having a strong plan behind your ethnographic study is important, but it’s just as crucial to not be rigid. Creativity is key—you need to leverage and combine a variety of ethnographic research methods like interviews, observation, enactment, storytelling and physical evidence to truly triangulate everything that is going on in a consumer’s life. We probably don’t have to mention that this can be a challenge within the short timeframe of a typical business ethnography. Fortunately, we have two key methodologies that can help:

How to Get to the Why Without Using “Why?”

There is a misconception that exists about the utilization of the word “Why” in the realm of ethnographic research. Most of you have probably heard of “The 5 Whys” popularized in the business arena by the Six Sigma DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) methodology to determine the cause of behavior by peeling away the symptoms in five increments. Although there is a probing process, there are no words that act as magical probing devices; in particular the word “WHY?”

So, why not WHY?

Why only limits your respondent to one form of response; typically one that starts with the word “because….,” which simply restricts the range of the answer. A better tactic is to ask open-ended questions, which remove limits on the responses and leave the respondent feeling they can tell you anything they feel is relevant and want you to know. Open-ended questions also give respondents the freedom and space to answer in as much detail as they like, and further detail helps to qualify and clarify their responses, yielding more accurate information and actionable insight. “Why” may be a simple way to ladder up, but the responses will typically be one dimensional, too rational, and close off the rest of the conversation—where the true insights might lie. It’s also seen by many respondents as “attacking”—not encouraging or inviting—and may lead to defensive answers.

So what can you use instead? It’s all about being indirect:

-Please tell me more about …

-What motivated you to …

-What are some reasons …

-What influenced you to …

-What did you say to yourself when …

-What factors got you to this point …

-Help me understand your thinking.

-What steps helped form the decision to…

2. Get to Emotion…FAST!

We know that people often don’t make logical choices and instead tend to go with their gut reactions, then rationalize their actions and decisions after the fact. Sound familiar? (We all do it.) Organizations find this troublesome, as it is not a productive business strategy. It’s not rational, and having a strategy is about having a rationale with clear logic. The thing is, rationality is never the decisive factor in business, and the best way to avoid being at parity with everyone else and escape the commodity trap is by adding emotional value. That is why when conducting an ethnographic study you need to get to emotion fast. Laddering works, but can be time-intensive. With so much emotional ground to cover, shortcutting the process can only be a good thing.

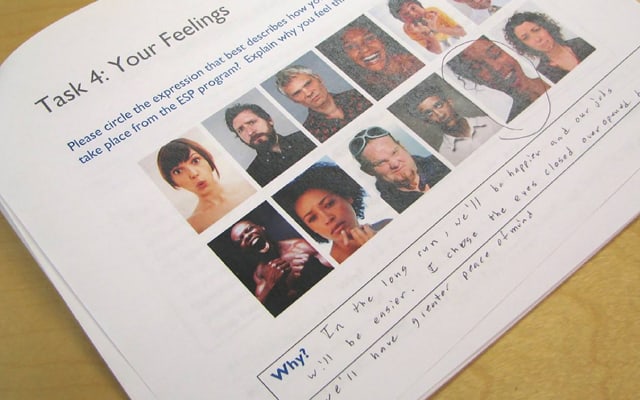

Enter “Emotion Cards,” seven simple cards that help you gain emotional literacy with the subject you are studying, shortcut the ladder and indirectly get to people’s emotions without asking that killer personal and awkward question to a relative stranger: “How do you feel?”

So how does it work? Emotion cards are simply what they sound like: photographs or illustrations that represent human emotion. The science of facial coding tells us that there are seven core emotions, with each emotion having its own meaning or script. The seven core emotions in Ekman’s set:

POSITIVE

Happiness – Happiness is the only true positive emotion. Happiness can range from fleeting pleasure to deep, sustained contentment. It is handsomely rewarded, and recognizing that people are willing to pay more for their dreamlike wants than needs can make for a killer value proposition.

NEUTRAL

Surprise – Surprise is neither inherently positive or negative. Its valence all depends on what we receive after the surprise is passed. We simply don’t know whether pleasure or pain awaits.

NEGATIVE

Fear – Fear is the single most important emotion as it is constantly monitored by consumers in the marketplace. Fear cuts through marketplace clutter like nothing else and is used to sell everything from life insurance to toothpaste.

Anger – Anger is what people use to attack or otherwise remove a barrier they believe is unfairly blocking their progress or undermining their identity. It is leveraged to escape some perceived danger.

Disgust – Disgust is the adverse reaction exhibited when we want to distance ourselves from an offensive source. Offerings that lack excitement inspire a mild form of disgust—boredom.

Contempt – Contempt is less basely physical than many other emotions and carries a moral sense of judgment attached to it, typically connected to the emotion of being deceived. This emotion reflects a deep disdain and is a hard one to recover from. You know your service or product has hit rock bottom when you’re registering contempt toward your brand.

Sadness – Sadness in business is expressed as “buyer’s remorse”. It’s a great emotion to probe more deeply on in an effort to understand the subject’s feelings of rejection and loss.

A lot of time is spent during ethnographies getting to the emotional quotient of a respondent. Asking open-ended questions and using emotion cards is a great way to make inroads to understanding the emotions that are the source of all human action and consumer behavior.

When we understand emotions and the context in which they are experienced, we can plan for and better manage the behaviors linked to them through the process of service and product design. This why ethnography is the beating heart of the customer experience. It brings us “up close and personal” in true empathetic connection to those messy emotions that drive behavior so we can truly determine what matters, how it matters, and when we should orchestrate it as a part of an experience. The success of any business turns on our ability to know both the rational and emotional drivers that build brand loyalty. Ethnography helps us get one beat closer to the truth.

REFERENCES

Handbook of Cognition And Emotion. Edited by T. Dalgleish and M. Power. 19999 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Emotionomics: Winning Hearts & Minds. Dan Hill. 2007 Adams Business & Professional

Ethnography: Step by Step. Fetterman, David M. – 2nd ed. Sage Publications, Inc.

People Insights at the Fuzzy Front of Innovation. Ramacker, Lucile & Un, Stefanie. 2006 Koninkliijke Philips Electronicsn N.V.

The 4 factors influencing consumer behavior, http://theconsumerfactor.com/en/4-factors-influencing-consumer-behavior/.

Blog | The Story of Telling, http://thestoryoftelling.com/blog/