LEARNING-BEING-DOING: Design Thinking for Chronic Disease Management

Worldwide, the healthcare industry is already dealing with serious change, from the legislative upheaval in the U.S. to aging populations and more sedentary lifestyles.

Another wave of issues to solve, however, stems from a rise in non-communicable, chronic conditions. In the U.S. alone, 117 million people — about half of all adults — are living with one or more, like cancer, diabetes or heart disease. As a result, the global healthcare industry is examining ways to help people better manage persistent conditions. We’ve found that design thinking can help — assisting the industry as they approach the complexities of this chronic epidemic.

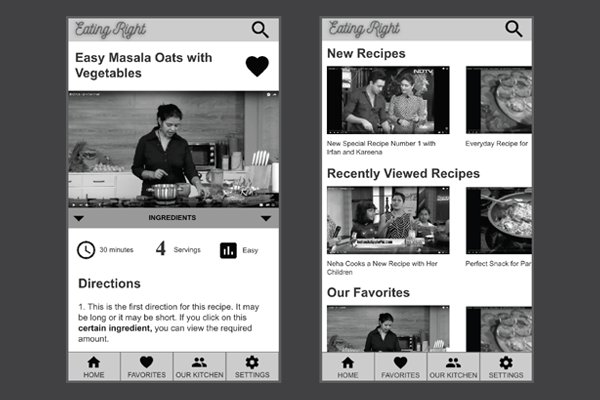

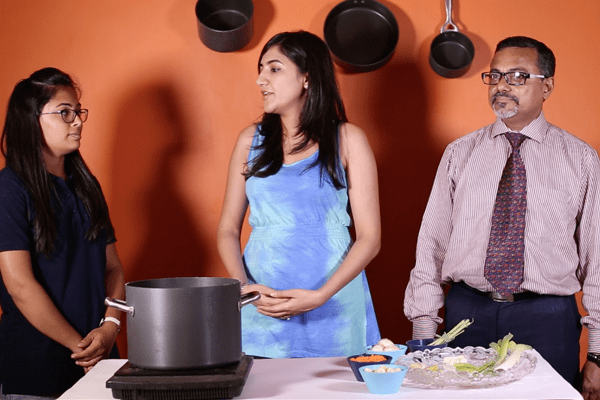

This year, I got the opportunity to add my voice to the discussion at the 2017 ACM CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Along with a team of colleagues, I presented research we had conducted through a Tandem Lab around diabetes management in five cities across India.

Through investigation of diet management (a critical component for those living with diabetes), we developed a unique research and design framework that zeroes in on the key areas that contribute to the challenges of chronic disease care. In shorthand, we call it Learning-Being-Doing.

By considering these three factors, we gained insight into people’s constraints preventing and factors promoting behavioral change that improves disease management. The result? A broader understanding of the context and situation facing both individuals with chronic illnesses and the families that support them.

While we created the framework to guide our investigation in India, it’s a relatable, holistic methodology that can apply to the research process surrounding any chronic disease, and inform the design of technologies designed to help control them.

One quick thing before we dive into the framework, however: I’ll mention some of the remedies that we heard in our interviews, but am not a medical professional nor qualified to take a stance on whether something is “correct” or not. We’re not making claims about which approaches are better or worse here, just presenting them as heard.

LEARNING

Defined as: How one seeks and gains information regarding disease management.

For any individual dealing with a lifelong disease, there are many supporters who participate in their care network, as well as countless sources of information they regularly encounter. Think about the last time you were sick with a cold and the various channels from which you received information: Your mom may have told you to eat soup and get some rest. WebMD.com might have recommended an over-the-counter antihistamine. An article posted on Facebook might have sworn by heavy doses of Vitamin C. Individuals with chronic conditions are no different, often receiving information through those same disparate mediums, and the credibility of that information (as well as whether it’s individualized or not), can become a factor in their ability to effectively manage their condition. To understand learning is to understand the different sources individuals and caregivers are willing to turn to for information, as well as their receptiveness towards the varied sources.

In our study, we did not find that our participants made specific efforts to search for diabetes-related information on their own, but several mentioned that they had encountered relevant advice on social media. For example, when asked about dietary changes, one participant shared that she had started using vijaysaar (a tree) as a remedy. She would soak pieces of the vijaysaar bark overnight, and in the morning, drink the soaking water. She followed this practice daily, and over time felt it had improved her condition. When we asked how she had learned to do this, she responded: “I saw it on the Facebook.”

Additionally, while doctors were seen as important, credible, and trusted sources of good advice, their recommendations were often viewed as impossible to follow. On diagnosis, diabetes patients are typically given a chart that lists specific meal times and recommended food options. Unfortunately, these regimens are often pretty foreign, bearing little resemblance to patients’ existing dietary habits. In our study, this contrast was enough to deter many patients from making real diet changes. Further, advice from doctors tended to place emphasis on foods to avoid rather than foods to include in one’s diet. Our participants complained that the doctor’s advice was always in the form of “less of this, less of that” as opposed to “do this” or “do more of that.” It’s a perception problem: As good as these recommendations might be, they leave patients at a loss and turned off by the negative.

Tips & Takeaways: When designing technologies for managing chronic illness, look at what kinds of information are viewed as meaningful and acceptable and why others are rejected or overlooked. To promote behavior change around specific recommendations, consider integrating indicators of credibility such as “stamps of approval” from medical professionals, reviews from patients who have tried a particular approach, or testimonials from well-known figures. Constructive suggestions for specific steps toward improvement should be included (i.e. “dos” and not just “don’ts”).

BEING

Defined as: How one is situated within his or her surroundings.

The being aspect of our framework concerns all the ways people and their behaviors are shaped by their immediate and interpersonal surroundings. Do they live alone, with roommates, or with close or extended family? Does the individual manage their disease alone, or do family members, friends or others help? Do gender or familial dynamics factor into the care situation? Consider wives who do all the cooking for the family: When it’s the husband who is diabetic, he may be the one receiving diet recommendations from his doctor, but it’s his spouse who really needs the information since she is the one making the food decisions. To understand being is to consider — and leverage — the power and influence of patient relationships and alliances.

In India, mealtime for diabetes-affected households can quickly become a balancing act. We found that most households sit down to eat their meals together and share the same dishes, so foods are rarely prepared separately for the person with the chronic ailment. Beyond consciously preparing appropriate meals and adjusting amounts of specific ingredients such as salt, those managing the kitchen strive to keep the preferences of the whole family in mind. Attempting to entirely omit staples like rice for example, can prove not only difficult, but nearly impossible, as everyone in the household has been accustomed to eating it regularly their entire lives.

We also repeatedly heard that eating meals outside of the home exponentially increased the complexity of managing one’s diet — something that’s certainly not unique to Indian diabetics. Dishes that specifically cater to people with dietary restrictions are scarce or unavailable in many places, and during social occasions outside the home, all bets are off as to what food might be available. In India—as in many places around the globe — it’s considered downright impolite to turn down additional helpings of food or decline when offered dessert. In our study, interviewees particularly bemoaned the intense social pressure they faced during special occasions to eat sweets or consume larger portions than they would at home.

Tips & Takeaways: Both care networks surrounding an individual and the amount powerful relationships influence a person’s lifestyle and disease management behavior must be considered when designing technologies that promote behavior change. Solutions should focus on helping people, and their families collaborate to make small changes rather than overhauling entire lifestyles.

DOING

Defined as: How one is willing and able to act.

Lifestyle modifications like diet alterations involve adjusting preferences and habits that are deeply entrenched. It’s no surprise then that adherence to recommendations is usually poor. There are a lot of reasons: People may have difficulty adapting due to lack of knowledge or contrasting viewpoints about what constitutes a healthy lifestyle. They may receive conflicting or impractical suggestions from medical professionals. Or, they might just lack motivation or support from family and care networks. Regardless, there’s often a powerful struggle to find balance between short-term pleasures and long-term health goals. Anyone who’s ever tried to drop a few pounds can certainly understand. To understand doing is to consider the daily struggle of a person controlling a chronic ailment — the ups, the downs, and every moment between.

In our study, we found that those dealing with diabetes tended to find ways to balance their desires for certain foods with their health requirements, but often tested their limits while doing so. For example, we observed that if people make a run of bad choices, they’ll exemplify this pattern of “crime and punishment”, indulging, then rolling back their diet for a few days until they find an opportunity to indulge again. There was also a general sense that one doesn’t have to completely give up the foods that bring great happiness and satisfaction, if one manages consumption and restores balance when lines are crossed. Beyond managing food intake, participants also widely claimed to control their diabetes through exercise. Walking was mentioned in nearly every interview as a critical method of control. Some even claimed walking after a meal would counteract the effects of bad dietary choices and stabilize their condition.

In addition to controlling food and exercising, managing stress — typically referred to as “tension” in India — was also seen as critical. One couple explained: “You shouldn’t take it too seriously. . . if you do dieting and all that you will become weak…then your diseases will increase. Just be tension-free.” Participants hinted at a balance between exercising great control over their habits and keeping a relaxed attitude for fear of exacerbating the effects of the disease. They expressed concern that being too worrisome or neurotic would increase stress and make their condition harder to control.

Tips & Takeaways: Understanding mental checks and balances and how they manifest should be a critical aspect of designing for disease management. Solutions should consider how health conditions impact an individual’s everyday actions, and in turn treat the patient, not just the condition.

The chronic disease management space is incredibly complex. Moreover, it’s a highly individualized affair, and often involves more than just the person with the disease. While medical management is critical, a cure or even symptom relief isn’t necessarily found in a pill. Lifestyle factors like diet and physical activity play a role, and it is self-management surrounding these elements that is often a key component of care. If design-thinking can help create better solutions for chronic disease patients, the key lies in viewing the issues from the patients’ perspective. Whether the end user is in India or Indiana, considering how people and care networks learn, be, and do in terms of handling their disease is key to designing better solutions to assist them.